Arvada’s 97,000 ash trees are in danger. The culprit? A green jewel beetle native to northeast Asia, called the emerald ash borer, which feeds on ash trees and reproduces in their bark crevices.

The borer’s larvae feed even more, wreaking havoc on the tree’s vascular system and causing dieback and eventual death.

The emerald ash borer (commonly called the EAB) was first discovered in the Homestead Park neighborhood near 64th Avenue and Sheridan Boulevard in 2020, but has now spread across town, according to Arvada’s City Forester Ian MacDonald.

“The spread has increased dramatically,” MacDonald said. “Last year, I would say, 64th and Pierce, it was pretty obvious that it was in that area. And then on the east side of town, the Tennyson and Bowles neighborhood, but now I’m seeing trees at 72nd and Sims that have symptoms of emerald ash borer.

“The time it took to go from the Homestead Park area to 64th and Wadsworth, it took about four years to get there, but now the difference between year four and year five is dramatic,” MacDonald said. “Everywhere I’m driving now, I’m seeing it. For sure on the east side of town, north to south, I’m seeing trees with symptoms or just dead trees.”

MacDonald said that the EAB typically takes five years to spread throughout a given area, and added that after that initial period, trees typically begin dying en masse.

“We’re five years into it, and the ‘mortality curve’ is what they call it; other states that have dealt with this have a pretty good tracking of how this moves,” MacDonald said. “The first five years is generally the build-up of emerald ash borer. And then five to 10 years is when you really start seeing the trees to start dying.

“We’re at that five-year mark, and mortality has really picked up,” MacDonald continued.

The EAB was first discovered in North America in 2002, with a population in Michigan that has killed tens of millions of ash trees in the state, according to the Michigan Invasive Species Program. Colorado is one of the westernmost satellite population sites for the EAB, though populations have also been found in Utah and Oregon.

The beetle’s presence in Boulder slightly predates its arrival in Arvada; the EAB was found there in 2013.

Boulder has approximately 70,000 ash trees, and through a variety of mitigation efforts — including chemically treating at-risk trees, introducing EAB predators and community educational outreach — the city was able to limit the impact of the pest, only removing 3,100 ash trees from 2013 to 2018, according to the city’s 10 year report on the EAB invasion.

MacDonald said that Arvada is working on utilizing some of the same procedures Boulder did in its mitigation efforts, treating at-risk trees and letting community members know that if they own ash trees, they should seek out trunk injections for larger trees and root system treatments for smaller ones.

“The trees on city property, we have done a full evaluation twice now in the last eight years, and we’re currently working on a third evaluation,” MacDonald said. “We aimed to save about half of the (ash) trees that were in our park system. We had roughly 1500 to start with. We’re down to about 1100 and we are treating just about 750 trees.

“Those are all treated in-house by our forestry staff, or they’re treated by licensed applicators from the Colorado Department of Agriculture, and we’ve been treating our trees every other year for the past five years,” MacDonald continued.

Those treatments have been mostly successful, MacDonald said, with 99% of treated trees surviving. The city lost two trees to the emerald ash borer this year, but plans to up the dosage of its trunk injection treatments to prevent further casualties.

For trees on private property, MacDonald suggested that homeowners contact service providers listed on Denver’s Licensed Tree Contractor List, which requires a thorough vetting process to be placed on, MacDonald said. He added that almost all service providers who operate in Denver will be able to come out to Arvada. The city of Arvada does not have its own such list.

MacDonald said signs of an EAB infestation might be difficult to spot at first, but generally show up after the first year with symptoms manifesting in canopy dieback, leaving a thin upper canopy and generally accompanying a lot of growth in the middle of the tree, called epicormic growth, which is the tree’s response to not being able to get enough nutrients.

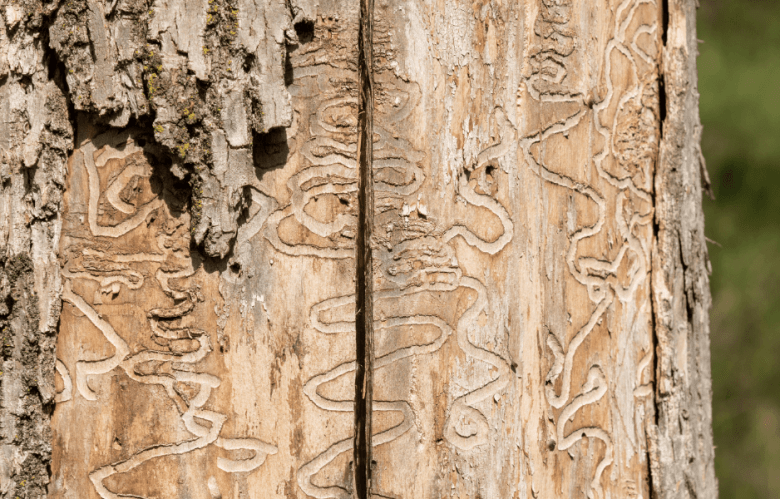

The emerald ash borer leaves D-shaped exit holes in trees after it leaves them. Its larvae leave serpentine patterns underneath the bark of the trees, called “galleries,” when they are feeding on the tree’s phloem in the winter, which eventually depletes the tree’s vascular system and kills it.

If people are seeing bark loss and galleries on your ash tree, it’s a sign that the tree is likely already dead, MacDonald said.

For now, MacDonald and his team are working on protecting the city’s ash trees despite the rapidly spreading population of the EAB and the fact that the mortality period seems to have begun — and will likely continue for the next five to 10 years.