Charles Lamb wanted to expand a natural spring on his land to create a stock pond for his animals. In 1960, when he started digging in northwestern Douglas County, his efforts were stalled by a discovery 13,000 years in the making: mammoth bones.

Lamb knew the discovery was out of his league, so he quickly contacted the United States Geological Survey, who confirmed his discovery. Lamb had found the tusk of a Columbian mammoth.

Shortly after, archaeologists from the Smithsonian traveled to Lamb Spring to excavate the site, finding the remains of at least five mammoths that came to the spring at the end of the last Ice Age.

Now, after excavations in the 1960s, 1980s and 2000s, Lamb Spring has quieted down. The site is empty most days, except for their monthly tours, or when Cameron Randolph — co-chairperson of the Lamb Spring Archaeological Preserve Board of Directors — goes out to mow in preparation of visitors.

Each month, typically on the first Saturday of the month, LSAP offers tours. At 9 a.m., Randolph and some volunteers lead visitors on a quarter-mile walk through the area, past a big depression in the land where the spring once was, to the site where the archeological excavations occurred.

At Lamb Spring, now in the Sterling Ranch area, excavations have occurred on a somewhat timely schedule. About each 20 years the land is dug up, unearthing new discoveries each time.

In the 1960s, along with the mammoth bones, archeologists found worked flint chips — a sign of human activity in the late Ice Age. During this excavation, they also discovered that the site had two layers. One from the Ice Age, roughly 15,000 years ago, which is referred to as Unit 1, and one from roughly 10,000 years ago, filled with evidence of human hunting, which is referred to as Unit 2.

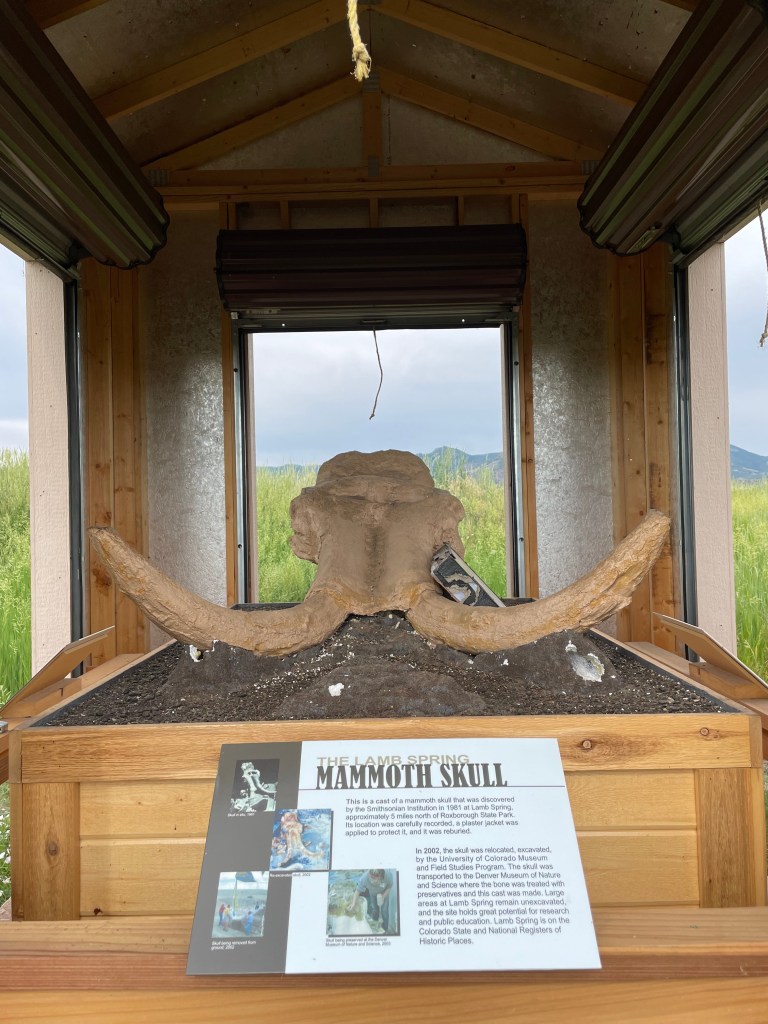

In the 1980s, excavation focused mainly on the older, Unit 1 layer. A full, juvenile mammoth skull was excavated, then reburied. In the newer, Unit 2 layer, more evidence of human hunting and bison bones were uncovered.

In the 2000s, the mammoth skull that had been reburied was once again uncovered. The skull was taken to the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, where it was exhibited, stabilized and cast. The cast of the skull was brought back to Lamb Spring, while the skull itself is in storage with DMNS.

Bones from Lamb Spring are fragile — while they may seem old, compared to some archeological discoveries, they’re young.

“If you dig up a dinosaur bone, it’s going to be fossilized,” said Randolph, “These are not fossilized entirely. They’re kind of in a state of fossilization. But they’re closer to bone.”

The mammoth remains’ fragility is where the cast comes in. Much sturdier, the cast is able to live at the spring year-round, offering visitors a glimpse into what lies beneath their feet.

The layers at Lamb Spring have etched two histories into the site. One of the late Ice Age, with mammoths — and possibly humans — walking the land. Another 5,000 years later of humans surviving by hunting bison.

During LSAP’s tours, docents try to bring visitors back to those times, imagining what life would have been like in Colorado for the humans and animals found in the spring. Visitors even get hands-on experience by throwing an atlatl, an early throwing spear that would have been used for hunting.

Looking out from Lamb Spring, in the distance, Randolph can see Lockheed Martin. He says that on tour days, the building reminds him why the site still matters.

“Lockheed Martin is trying to define what the future looks like, and we’re actively trying to describe what the past looks like,” Randolph says. “I think it’s kind of important to talk about where we’ve been, while they’re talking about where we’re going.”

Randolph thinks that learning from the past can also help people prepare for the future.

“We try to stress the idea that you can learn from the past,” he says, “that there’s things we can be doing, and there’s things that we should be doing to protect nature. It shows how valuable some of those natural resources that we have are.”

More information on tours can be found at https://www.lambspring.org/free-tours/. Upcoming tour dates are July 5, Aug. 2, Sept. 6, Oct. 11. Tours start at 9 a.m. and typically conclude by noon.